“Talons gripping the edge of the nest

wings spread, gauging the wind

the young osprey pushes off,

soaring.

With each practice flight,

the young bird returns to the nest

and places at his mother’s feet,

one twig.

Every evening

in the dark, bright, quiet

of the moonlight the young bird

sleeps.

While his mother,

taking his twig,

builds a nest in

his heart.

So when he flies away

wherever he lands

the young bird

is home.”

Up here in Maine, the tides go out, and the rocky shoreline appears and then the water comes back in, right up to the shore. It may be a small thing in the grand events of the world, but there is such solace in that constancy—in knowing that as you watch the water go away from shore, you also know it will return. It is a twice-daily event, which adds to the experience and learning of the constancy that nature provides. The moon disappears from view and it comes back. The sun disappears from view and it comes back.

The very best of parenting is like the constancy of the tides. Children are their own force of nature. It is the sacredness of constancy that helps hold them and shape them. You are the tides for your children. You are the air. You are the sun and moon that their world revolves around.

Constancy isn’t cool, or hip, or sexy, or most importantly, marketable. “Hey, let me sell you a ticket to watch the tide roll back in over the course of hours!” Constant moments aren’t Facebook postings: The First Day of School, Graduation, Soccer Championships, Recitals. These are all wonderful and I personally love to see the pictures whether I know you or your kids or not: there is such joy and humanity in those photos. But these aren’t pictures of tides, they are pictures of special events: like meteor showers and rainbows—the colorful moments of life that occur, but you catch them and enjoy them when you can.

I can market Disney and make you feel great about being the kind of parent who takes their kid to the Magic Kingdom. But there is no equal marketing for you getting the 5th glass of water that night. Even if that 5th glass of water is actually the thing that will become part of the fabric of your daughter. Even if that act is the nutrient all children need. Much like there is marketing for Sugar Cereal and Junk Food and not carrots.

The sacredness of parenting rarely shows up in pictures, it’s hard to share on Facebook, it’s hard to see when you are in it. The sacredness of the everyday—the mundane, routine, constant all-of-it—that is what makes the warp and weft threads that create a person. The sacredness of the everyday of parenting is what makes up the fabric of who a child is, the self and worldview they rest in, the blueprint for relationship they will carry with them.

There are no pictures of you putting a Band-aid on arm that actually doesn’t have a cut on it. Of picking up cereal, or socks, or Legos off the floor. The endless laundry, dishes, trash. There are no pictures of the hundredth viewing of ‘Frozen’ or reading of ‘Goodnight Moon.’ The seventeenth math problem. The tears after a fight with a friend. There are no pictures of bedtime after bedtime, and breakfast after breakfast. Of the wrestling matches of putting on socks and finding shoes and NO I WON’T WEAR THAT COAT. Your ability to shepherd all of these things are the tides that come in and out.

I have such a perfect image of my niece as a toddler, all wrapped up in a towel after a bath at night, sitting on my sister-in-law’s lap. She was just hanging out, her wet hair slicked back, pink cheeks, sucking on her fingers, her blue eyes looking out, but not all that interested in the grown-up conversation around her. This was one of those sacred moments of childhood—where it was nothing special—to the outside world--but it was everything special to her inside world. This is the sacred everyday act of parenting. The absolute building blocks of safety and security and contentment and confidence. This was just the end of bathtime, the beginnings of bedtime, the transitions of the everyday. But they are the bricks of healthy capacity—put thousands of them together and you have a foundation that can hold anything.

The very definition of this constancy is that you can take it for granted. You believe in its existence utterly. I don’t worry whether the tide will come back in. I know it will. I don’t worry that the moon will reappear. I know it will. And the constancy you provide your children is something that they can and should take for granted. I am not talking about material things or that they will never learn to pick up their own Legos. I am talking about the constancy of asking for help and hearing a response (even if that response is age-appropriately telling them they can do it themselves). I am talking about the constancy of nighttime after nighttime of good-night, and morning after morning of good-morning, of bath, books, and bed; of lunch boxes and walks to the school or bus stop; of someone who listens again and again to the same story, the same movie, the same knock-knock joke. Of whatever it is we will figure it out.

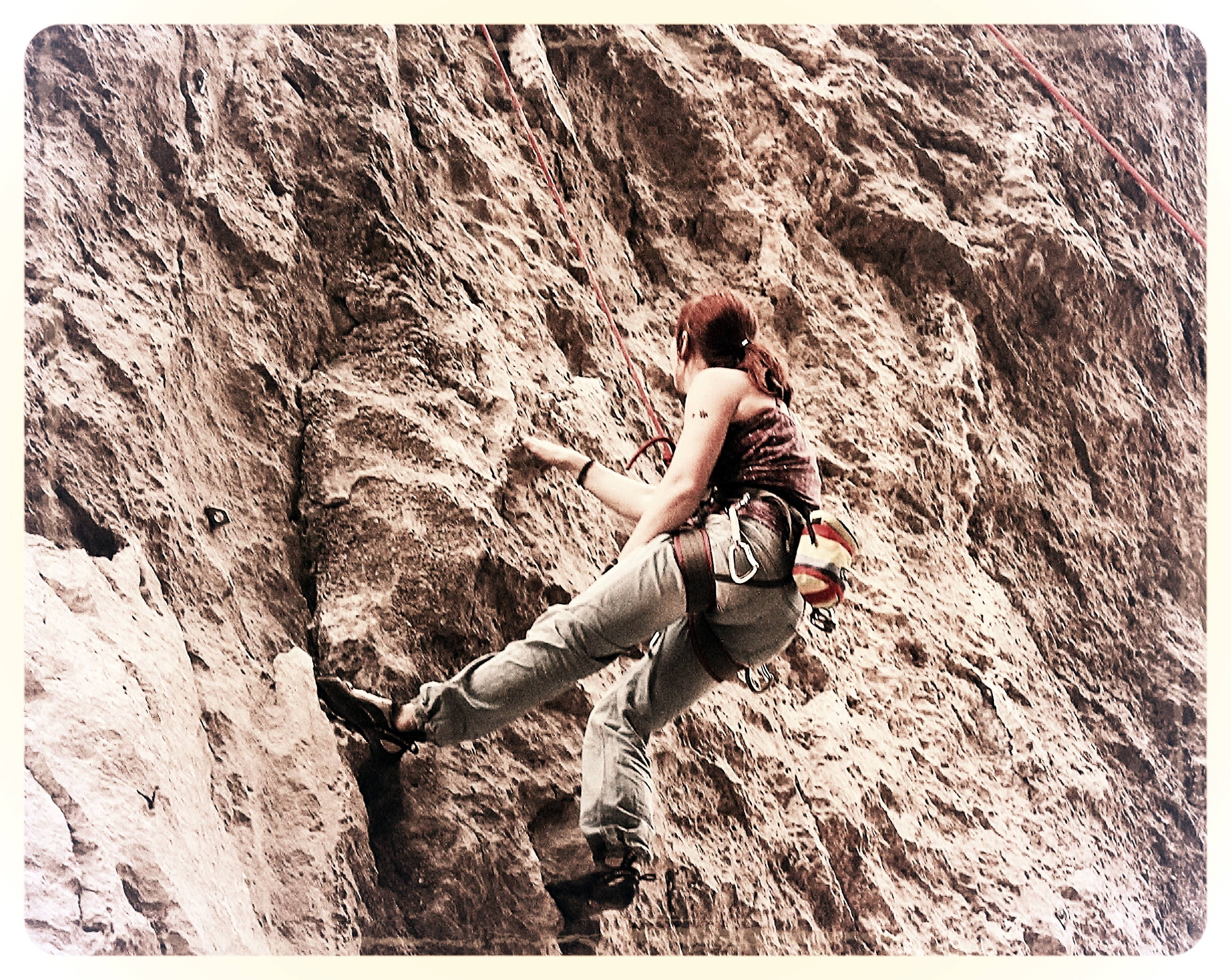

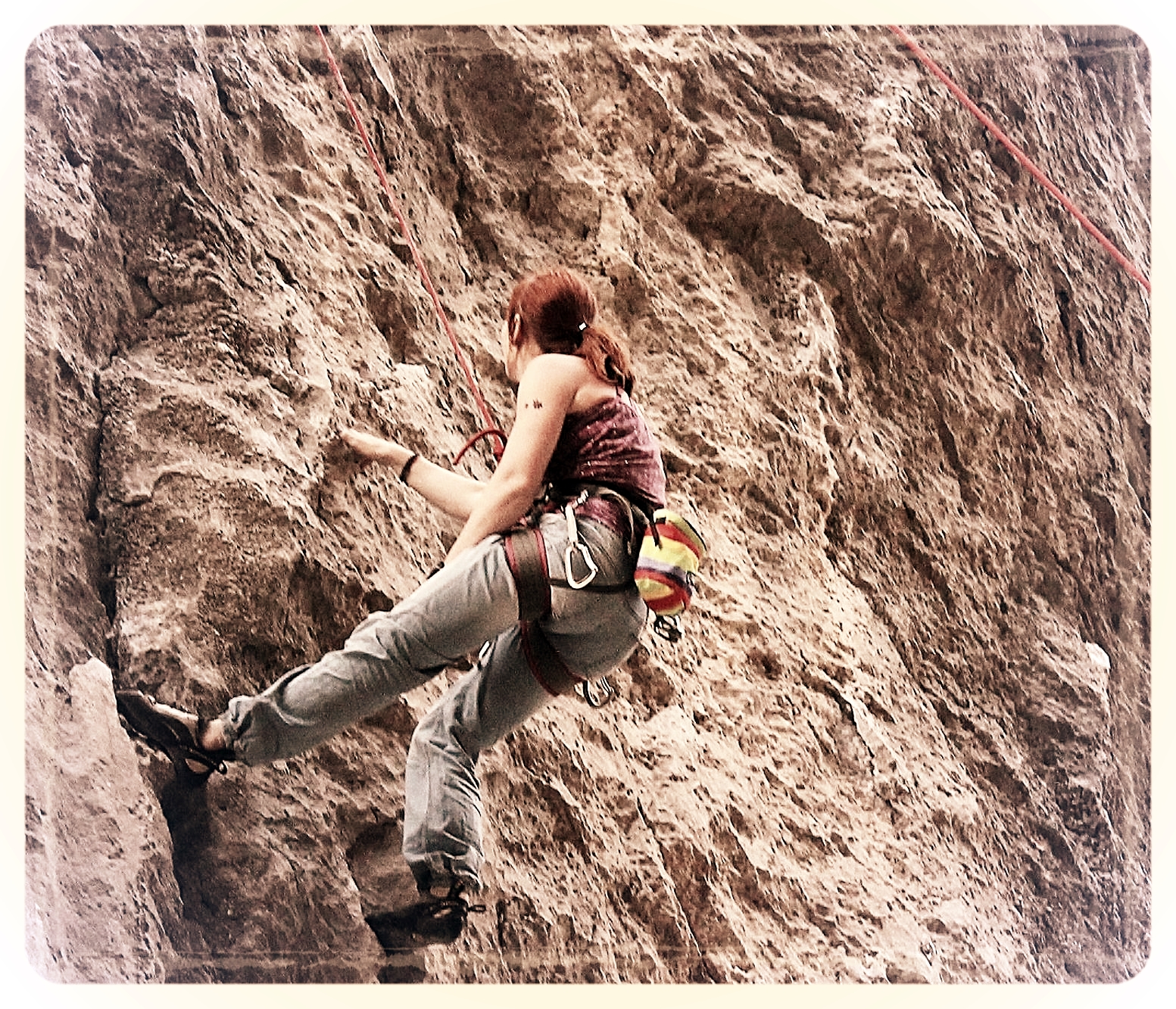

Your super powers are your indestructability and your ability to show up over and over again. What makes your work important are the thousands and thousands and thousands of small threads that you weave around their heart, their soul, their growing being. This is what makes constancy sacred. You are building a space in their heart for this constancy—for this ability to hold the world and themselves. You are building this constancy in them so they can hold the rest of the world--which so often isn’t constant. Like the poem of the Osprey above with each mundane, routine, sacred constant act, you are building a nest in their hearts that they can return to for strength and comfort for the rest of their lives.

© 2016 Gretchen L Schmelzer, PhD